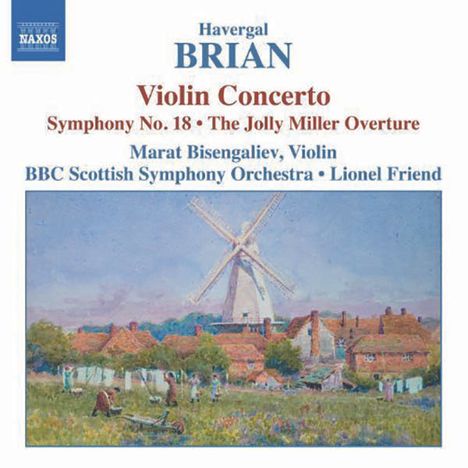

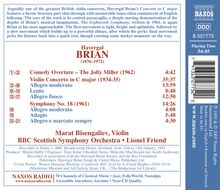

Havergal Brian: Symphonie Nr.18 auf CD

Symphonie Nr.18

Herkömmliche CD, die mit allen CD-Playern und Computerlaufwerken, aber auch mit den meisten SACD- oder Multiplayern abspielbar ist.

(soweit verfügbar beim Lieferanten)

+Violinkonzert; Jolly Miller-Ouvertüre

- Künstler:

- Bisengaliev, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Friend

- Label:

- Naxos

- Aufnahmejahr ca.:

- 1993

- Artikelnummer:

- 1964351

- UPC/EAN:

- 0747313277520

- Erscheinungstermin:

- 18.4.2005

At different points in his career Havergal Brian wrote three works which he described as “comedy overtures”. Each of them, despite the programmatic connotations of their titles, possesses a purely abstract form. Doctor Merryheart (1912) is a set of symphonic character-variations on an original theme; The Tinker’s Wedding (1948) is a ternary scherzo-and-trio design. The third and last “comedy overture”, The Jolly Miller (1962), is a binary form comprising an extended introduction, a theme, and a short series of free variations. The theme itself is one Brian had known since his childhood, and although several of his works (not least the Violin Concerto on this disc) allude to the character of English folk-melody, this is the only occasion on which he consciously employed a folktune as a thematic subject. The tune, variously described by collectors as a Cheshire folksong or a 16th century popular song, is sometimes known as “The Miller of Dee”, and sometimes by the title Brian chose for his Overture.

That title is ironic: from Chaucer’s miller in The Canterbury Tales to Tolkien’s Ted Sandyman in The Lord of the Rings, millers receive a poor press in English literature. The song’s protagonist is a regular misanthrope, his constant refrain “I care for nobody, no not I, and nobody cares for me”. As if in confirmation, Brian once confessed that the words reminded him of two millers he had known as a boy in Staffordshire: the curmudgeons hated each other! But there is nothing misanthropic about his little Overture, which he composed in the spring of 1962, at the age of 86, as a present for the family of his daughter Elfreda, while he was working on his 20th Symphony.

The key of the Overture is G: Brian takes full advantage of the harmonic piquancy provided by the folksong’s mixed mode, which combines the minor 3rd with a major 7th. Almost half the work is taken up with a bustling, high-spirited introduction [1] in 2/4: this evolves its own figures, melodically but not rhythmically related to the Jolly Miller theme which eventually, after a quiet cadential passage, appears in 6/8 in suitably lugubrious tone son the woodwind [2]—and in a curious “shorthand” form, omitting the repeat of its first strain, as if Brian was relying on his memory (as he probably was) rather than any printed folksong-collection. There follows a swift succession of informal but highly energetic and rhythmic variations, making much use of the large complement of percussion, before a final uproarious statement of the tune. Brian never heard The Jolly Miller performed. It was premièred in November 1974 in the USA, by the Main Line symphony Orchestra of Philadelphia under their conductor Robert Fitzpatrick. Its first UK performance took place in Southampton the following month. Both of these were with amateur forces, and the present recording constitutes the Overture’s first professional performance.

After the completion of his Fourth symphony, Das Siegeslied (Marco Polo 8.223447), in 1933, Havergal Brian embarked on the composition of a similarly large-scale Violin Concerto. He himself had learned the violin as a child, and all four of the symphonies he had written up to that point feature important episodes for solo violin, so a concerto was certainly a logical project for him to tackle. He began to sketch it in the spring of 1934, and completed a draft of the entire work in short score on 7 June.

The following day his endemic bad luck scored its latest victory. As usual, Brian travelled to work as Assistant Editor of the journal Musical Opinion by train from South London to Victoria Station; on arrival, he found that his case, containing the entire existing material of his new Concerto, was missing—either lost or stolen. Though he advertised in three national newspapers for the return of his property, the Concerto was never recovered. Brian made a fruitless search of the lost property offices; as he recalled wryly some years later “When I went to Waterloo station inquiring—the man at the counter suddenly turned round & shouted to another Railway man behind ‘You got that work Joe?’ & that was the last I heard of the Violin Concerto...”

Nothing daunted, Brian set to work again almost immediately: not, it seems, to reconstruct the lost Concerto, but to write a second one using the themes he remembered from the first. This is entirely plausible given the highly memorable nature of so much of the thematic material of the existing Concerto, whose short score was finished in November 1934. Brian completed the full score on 8 June 1935—a year to the day since the work’s predecessor had disappeared. At first he called this new composition Violin Concerto No. 2, and gave it a title—The Heroic. Later, however, he dropped both numeral and epithet; history knows only a single Havergal Brian Violin Concerto, in C major.

That had been the nominal main key of the Fourth Symphony also: but whereas the Symphony’s tonality was extremely fluid, merely beginning and ending in firm areas of C that held the billowing structure in place like tent-pegs, all three of the Concerto’s movements are centred on C—minor in the first movement, major with a flattened 7th in the slow movement, firmly major in the finale. The structural contrast is equally great. The Symphony conforms to no traditional formal patterns and obsessively metamorphoses its material into ever new shapes, while the Concerto’s movements are spacious architectural designs, two of them clearly related to sonata forms and customary concerto behaviour, with some of the most direct and “tuneful” melodic writing in Brian’s entire output. There is no doubt that the great Romantic concertos, up to and including the Elgar, served him as a generalized template for his own essay in the form.

These comparatively conventional features are balanced, however, by an exploratory and unconventional attitude to the famous “concerto problem”: the treatment of the solo instrument and its relationship to the orchestra. Coming after a series of large-scale Symphonies for very large forces, Brian’s handling of the orchestra remains fundamentally symphonic. He uses a smaller orchestra than for those first four Symphonies, but this still involves triple woodwind, full brass, harp, strings, and much percussion; the scoring is often weighty or very full-textured, and highly contrapuntal. His solution—or perhaps deliberate non-solution—to the inevitable difficulties of balance is to write a solo part that fights back: a heroic bravura part of extreme difficulty, requiring the powers of a first-rate virtuoso with the big tone of a Kreisler or an Albert Sammons. In one sense the Brian Concerto is what Josef Hellmesberger said of Brahms’s: “written against the orchestra”. But in another it bears out Hubermann’s rejoinder “for violin against orchestra”. Although the part is of extreme difficulty, full of cruel octave writing, tricky and unusual passage-work, and a taxing use of extremes of the register, it is nevertheless conceived with a profound and intimate knowledge of what the instrument can do if pushed hard enough. The fact that, a few years later, Brian wrote in warm admiration of the Schoenberg Concerto—a work many violinists then be1ieved unplayable—is sufficient evidence of his attitude to composing for a soloist. But frequently he allows the violin moments of endearing simplicity: and his approach can be the reverse of “soloistic”, sometimes blending the violin in unison with the timbres of a large woodwind body.

Brian’s Concerto begins in media res [3]: a single bar of serpentine chromatics on unison strings, and the soloist strikes in with a sweeping descending phrase in octaves, touching off a welter of stormy orchestral polyphony. The various symphonically-metamorphosing motifs (one of them an impressive Con passione figure for the violin against sonorous brass chords) accumulate into a lengthy and complex “first subject group” through which the soloist plots a fervent and voluble course, interweaving among and soaring above the various contrapuntal strands. Suddenly the storm is stilled: there appears instead a second subject [4] in the classical G major, and in utter expressive contrast. Almost at once this tender, folksong-like tune with its spare and delicate accompaniment is turned into an expansive and lyrical waltz-like development of itself in compound time, with a tiny, mysterious codetta where the violin spirals up to a stratospheric high E.

At which point [5] common time returns and the development-section proper strikes in with angular contrapuntal transformations of the second subject in the orchestra alone, soon joined by the violin with its own brand of pyrotechnics. There follows a grandiloquent, rather Elgarian tutti [6] developing the various motifs of the first subject; and this paves the way for what is in effect—though not marked as such—a capricious accompanied cadenza [7]. This culminates in a dramatic octave descent, and the coda begins with a reminder of the serpentine figure from the work’s very opening, before the woodwind state a calm, mellifluous Lento theme in rich harmony [8]. Though this feels like an entirely new idea, it is in fact a radiant transformation of the salient elements of the once-so-turbulent first subject. Sweetly and seraphically the violin takes it up, and reminders of both the first and second subjects are woven into a dreamily romantic discourse before the movement closes with astern reminder of its opening.

The slow movement, anticipating by some years that of Shostakovich’s First Concerto, is cast as a passacaglia, on a lyrically ruminative eight-bar theme announced by cellos and basses [9]. This is one of Brian’s noblest and most unified structures, and at the same time a superb demonstration of his powers of variation. Although the theme establishes the melodic and harmonic background of the ensuing 15 variations, it is itself continuously varied, appearing not just in the bass but in all the orchestral registers; and the variations themselves expand through canonic overlapping and restless changes of time-signature. The first three, relatively orthodox, see the violin taking up and then decorating the theme, but variation 4 brings a full-orchestral tutti [10], developing it in symphonic style. The violin, resuming in variation 5 in dialogue with solo flute, works up increasing fervour through the next two variations, culminating in a further one for orchestra alone which constitutes the movement’s central climax. A sense of exalted lyricism prevails in variation 9 [11] with its tranquil lapping rhythm, and then the solo line takes on increasing eloquence throughout variations 10 and 11 as it rises to yet another purely orchestral variation, strenuous and contrapuntal, climaxing in a resplendent brass version of the theme. The mood returns to one of still serenity [12] with two variations for violin and strings only—the first rhapsodic, the second of extreme simplicity. Flute and harp are added for the 15th and last variation, which forms a coda of peaceful intimacy.

The finale begins [13] with the violin’s bold statement of a forthright, striding C major theme with intriguing cross-rhythms. Starting out in 4/4, this almost immediately metamorphoses into a dance-like 6/4 and initiates a stream of coruscatingly athletic music that constitutes the movement’s first subject. As the excitement rises, the orchestra insists on going back to the opening idea (as a brass fanfare) and launches into a full-scale tutti development-cum-counterstatement of the first subject before the second subject has even appeared.

When eventually it does [14], in solo violin against pizzicato strings and harp, it proves to have been well worth waiting for—an irresistibly “English” march-tune in E major, which the soloist develops and embellishes with nonchalant good humour. Soon the music withdraws into a hushed, mysterious Lento episode [15], where the soloist, as if in a trance, spins a smooth, high, themeless stream of figuration against a drowsy ostinato in harp, low strings, and muted horns. It emerges from this into a slower development of the second subject, which the orchestra then continues on its own, and leads us up to the Concerto’s principal cadenza [16]. This one, largely based on the finale’s opening subject, is unaccompanied until its final bars and contains, as appropriate, perhaps the most taxing bravura writing in the entire work. Soloist and orchestra then collaborate in a compressed recapitulation of the first subject [17], the violin rising ever higher in its expressions of elation and finally zooming up to its highest possible C. After which—unlike any other major violin concerto—the soloist plays no further part in the proceedings: the work ends with the second-subject march, finally given a full, triumphant orchestral treatment.

Like most of Brian’s important scores, the Violin Concerto had to wait a long time for its first performance, but it found a champion at last in the late Ralph Holmes, who was the soloist in a BBC studio première broadcast on 20 June 1969, with the New Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Stanley Pope. Holmes also recorded a later performance for the BBC and played the Concerto in public at St. John’s Smith Square, London in 1979. In all his performance she made some simplifications of Brian’s cruelly taxing solo part, but for the present recording Marat Bisengaliev has restored it exactly as the composer intended.

Brian was by no means as unrealistic or inflexible in his instrumental demands as he is often portrayed—as is illustrated by his 18th Symphony, composed between February and May of 1961, immediately after the completion of Symphony No. 17 (Marco Polo 8.223481). At this precise time preparations were in hand for the world première of Brian’s enormous Gothic Symphony (Marco Polo 8.223280-1), which was to be conducted by Bryan Fairfax on 24 June that year. While discussing that project with the composer, Fairfax had asked Brian if any of his symphonies was scored for forces small enough for him to programme with his largely amateur Polyphonia Orchestra. None of them was; but Brian quizzed Fairfax on the precise instrumentation the Polyphonia could field and then, unknown to the conductor, set to work to compose a symphony of the required orchestral size. No. 18—dedicated to Bryan Fairfax and the London Wind Music Society (the core performing body for the Gothic première)—is thus the only one of the 32 Havergal Brian Symphonies which merely requires double woodwind (the various extras being doubled by the second players). Otherwise the brass complement is standard apart from the absence of a third trumpet, and the percussion body, which is kept very actively employed, is as large as Brian’s norm at this period. Bryan Fairfax conducted the world première with the Polyphonia Orchestra at St. Pancras Town Hall, London, in February 1962, and also directed the first professional performance, a BBC studio recording broadcast in June 1975.

After the series of one-movement Symphonies, Nos. 13-17, which Brian had composed in the preceding months, No. 18 signalled a new departure with its three separate movements, classical dimensions, and even suggestions of classical forms—though these are modified by the process of continuous development. It does not, however, signal any relaxation of expression. This is a concise, sardonic, driven work whose march-like outer movements enclose a bleak central elegy. Formally speaking, the Allegro moderato first movement [18] is a rather Haydn-like design, an implicit sonata-movement with but one subject. That subject, however, is a hard-bitten, almost Mahlerian march, conceived in a single tempo, growing new extensions at each appearance and stripped ever further down to its skeletal basics as the movement proceeds.

The slow movement [19] is the first example of a kind Brian was to develop in several of his later symphonies, which gradually takes shape from various neutral, drifting figures in different parts of the orchestra, and is welded into a unified expression of increasing intensity and inevitable direction. The mood is oppressive, tinged with tragedy; the sense of a slow, funereal march emerges in contrast to the fast military march of the previous movement. The music finds individual voices to articulate its grief in a solo viola and a solo flute, but the movement concludes by building up an angry crescendo for the full forces, dominated by brass and percussion.

With something of an emotional jolt, the finale then begins [20] as an exuberant quick march in 3/4 time. Some grotesque and hectic episodes nevertheless darken its jollity, and for a moment it teeters on seriousness as Brian produces a broader 4/4 variation of its main subject in Marcia lento tempo [21]. The Allegro tempo soon reasserts itself, but truculence and scherzando good humour remain intertwined. The angrier mood wins the day in the coda, whose brazen fanfare rhythm brings the proceedings to a precipitate end.

© 1993 Malcolm MacDonald

Rezensionen

J. Salau in FonoForum 7/94: "Im Zentrum dieser CD steht sein ausladendes Violinkonzert. Der Solopart ist derartig mit Höchstschwierigkeiten gespickt, dass in den wenigen Aufführungen bislang nur vereinfachte Versionen gespielt wurden. Großes Lob daher für den aus Kasachstan stammenden, heute in England lebenden Geiger Marat Bisengaliev, der diesen "Brocken" nicht nur in technischer Hinsicht erstaunlich sicher bewältigt."Disk 1 von 1 (CD)

-

1 The Jolly Miller (Concert Overture No. 3): section 1

-

2 The Jolly Miller (Concert Overture No. 3): section 2

-

3 Violin Concerto in C major: I. Allegro moderato: section 1

-

4 Violin Concerto in C major: I. Allegro moderato: section 2

-

5 Violin Concerto in C major: I. Allegro moderato: section 3

-

6 Violin Concerto in C major: I. Allegro moderato: section 4

-

7 Violin Concerto in C major: I. Allegro moderato: section 5

-

8 Violin Concerto in C major: I. Allegro moderato: section 6

-

9 Violin Concerto in C major: II. Lento: section 1

-

10 Violin Concerto in C major: II. Lento: section 2

-

11 Violin Concerto in C major: II. Lento: section 3

-

12 Violin Concerto in C major: II. Lento: section 4

-

13 Violin Concerto In C Major: Iii. Allegro Fuoco: Section 1

-

14 Violin Concerto In C Major: Iii. Allegro Fuoco: Section 2

-

15 Violin Concerto In C Major: Iii. Allegro Fuoco: Section 3

-

16 Violin Concerto In C Major: Iii. Allegro Fuoco: Section 4

-

17 Violin Concerto In C Major: Iii. Allegro Fuoco: Section 5

-

18 Symphony No. 18: I. Allegro moderato

-

19 Symphony No. 18: II. Adagio

-

20 Symphony No. 18: Iii. Allegro E Marcato Sempre: Section 1

-

21 Symphony No. 18: Iii. Allegro E Marcato Sempre: Section 2

Mehr von Havergal Brian

-

Havergal BrianSymphonie Nr.2CDAktueller Preis: EUR 14,99

-

Overtures From The British Isles Vol.3CDAktueller Preis: EUR 19,99

-

Havergal BrianSymphonie Nr.13CDAktueller Preis: EUR 15,99

-

Havergal BrianSymphonie Nr.1 "The Gothic"2 CDsVorheriger Preis EUR 29,99, reduziert um 0%Aktueller Preis: EUR 22,99