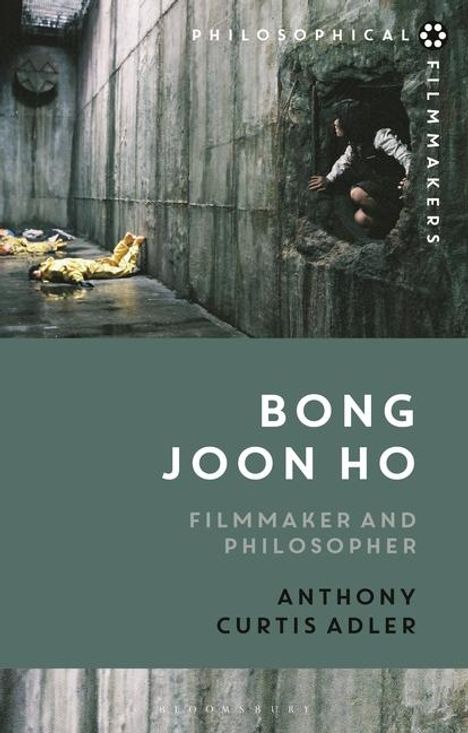

Anthony Curtis Adler: Bong Joon Ho, Gebunden

Bong Joon Ho

- Philosopher and Filmmaker

(soweit verfügbar beim Lieferanten)

- Verlag:

- Bloomsbury Academic, 12/2025

- Einband:

- Gebunden

- Sprache:

- Englisch

- ISBN-13:

- 9781350414655

- Artikelnummer:

- 12145991

- Umfang:

- 338 Seiten

- Gewicht:

- 454 g

- Maße:

- 216 x 138 mm

- Stärke:

- 25 mm

- Erscheinungstermin:

- 11.12.2025

- Hinweis

-

Achtung: Artikel ist nicht in deutscher Sprache!

Weitere Ausgaben von Bong Joon Ho |

Preis |

|---|---|

| Buch, Kartoniert / Broschiert, Englisch | EUR 37,25* |

Klappentext

With the release of Parasite(2019), winner of the Palme d'Or and an Academy Award for Best Picture, the South Korean director Bong Joon Ho secured his place as one of his generation's leading filmmakers. While scholars and critics have long appreciated his penetrating critique of Korean society and global capitalism, this book presents the first cohesive philosophical analysis of his first seven feature-length films. It argues that Bong's cinema not only engages with philosophy, but is radicallyphilosophical. Writing as an intimate outsider to Korea, a "resident alien" married into a Korean family, and teaching at Bong's own alma mater, Anthony Curtis Adler explores Bong's visionary and re-visionary treatment of spatiality, temporality, myth, memory, genre, and the semiotics of monstrosity.

Adler argues that for Bong Joon Ho, cinema doubles the ambiguity of philosophy, presenting the aesthetic means to represent anarchic motions and movements. While it can capture and contain them, subordinating them to an overarching order, it can also free them to appear in their anarchy. From the humble apartment building of Barking Dogs Never Biteto the train in Snowpiercerand Parasite'smansion, Bong's films stage interior spaces as representations of a cinematic apparatus that is, ambiguously, site of both imprisonment and liberation.

Even while confronting globalism head-on, Bong's films never cease to engage with the specific challenges faced by modern Korea, and, above all, the struggle of the Korean people for political representation and economic justice.